news

What Officers Are Actually Up Against in 2026 (And Why It’s Bigger Than Staffing)

- TL;DR

- 1. A Growing Federal Presence Without Local Context

- 2. Lawsuit and Personal Liability Pressure Never Really Turns Off

- 3. The Trust Gap Between Officers and Communities Is Widening

- 4. Burnout From Calls That Never Make the Record

- 5. Feedback Still Arrives Almost Exclusively When Something Goes Wrong

Signup for Updates

Share

TL;DR

- This isn’t just about staffing anymore. Officers are walking into 2026 carrying pressure that shows up before a call even starts.

- Federal activity, national headlines, and social media are shaping local interactions, often without local officers having context or control.

- Lawsuit and personal liability pressure feels constant now, even on routine, by-the-book calls.

- Most of the work that causes burnout never shows up in reports, quiet de-escalations, tense conversations, calls that “went fine.”

- And feedback still mostly arrives when something goes wrong, leaving officers guessing how they’re actually doing.

Table of Contents

When people talk about the future of policing, the conversation usually jumps straight to numbers: staffing shortages, budgets, response times.

Those things matter. But lately, the realities shaping the job are extending beyond internal metrics, influenced by national headlines, shifting enforcement dynamics, and public scrutiny that officers feel long before it shows up in official data.

Taken together, those forces are creating a set of pressures officers are carrying into 2026, something we want to take a moment to lay out here.

1. A Growing Federal Presence Without Local Context

Lately, a lot of officers are finding themselves working against a much louder backdrop than they used to. Federal Presence in their communities. For many, it’s also unfamiliar. Outside of storm response or large-scale emergencies, this level of federal involvement is something they’re encountering up close for the first time.

In some communities, federal enforcement activity has become more visible in day-to-day environments, not just during crises, but as part of the regular backdrop of policing. When that happens, local officers often end up responding in the middle of situations they didn’t initiate and don’t have full context on, showing up to calls where emotions are already elevated and information is limited.

We’ve seen this play out in places like Minneapolis, where recent headlines around ICE-involved shootings and federal operations sparked protests and strong community reaction. Even when local agencies weren’t involved, officers still felt the impact on shift, answering questions, navigating tension, and handling everyday calls shaped by what people were seeing and sharing in the news.

That puts officers in a tough spot. They’re expected to de-escalate, reassure, and keep things moving forward, often without advance notice or clear answers, while still being the most visible presence in the room.

As we discussed recently with Eric Tung, most officers got into this work to help their communities, because they care and want to protect and build trust with their neighbors When outside dynamics introduce stress or confusion into those interactions, it can quietly erode progress that took years to build, even when officers themselves haven’t changed how they show up.

In effect, now even in the communities they serve, officers are finding themselves standing in the middle of events they didn’t set in motion.

2. Lawsuit and Personal Liability Pressure Never Really Turns Off

For many officers, legal pressure no longer feels tied to rare or extreme incidents. It feels constant. Civil lawsuits used to be something you worried about after a major event. Now, officers describe it as a background risk attached to nearly every call, even when they’re trained, compliant, and operating squarely within policy. What’s changed isn’t the existence of litigation, it’s how early and how often it enters the picture.

Formal complaints tend to surface too late to be helpful. In many cases, officers feel interactions move directly into legal territory, skipping any meaningful opportunity for course correction or context. The concern isn’t just use of force, it’s tone, wording, pacing, and perception, all of which can later be scrutinized through a legal lens.

In places like Salt Lake County, public reporting shows more than $13 million paid out in civil rights–related settlements between 2012 and 2022. Officers don’t need that number explained to them. They already know it, and they carry that awareness into everyday decision-making.

Doing everything “by the book” no longer feels like meaningful protection. It feels like the baseline requirement just to stay in the game.

Officers talk about second-guessing routine decisions, slowing interactions down, or operating under the assumption that even a well-handled call could later be reviewed, challenged, or escalated into a legal process. That weight shows up immediately, not after something goes wrong.

Early indicators, context, feedback, small signals from the community, can slow that slide long before an interaction reaches lawsuit territory. Without them, officers are left navigating blind, carrying legal uncertainty from call to call.

And like many of the pressures officers are heading into 2026 with, this one doesn’t clock out at the end of a shift.

3. The Trust Gap Between Officers and Communities Is Widening

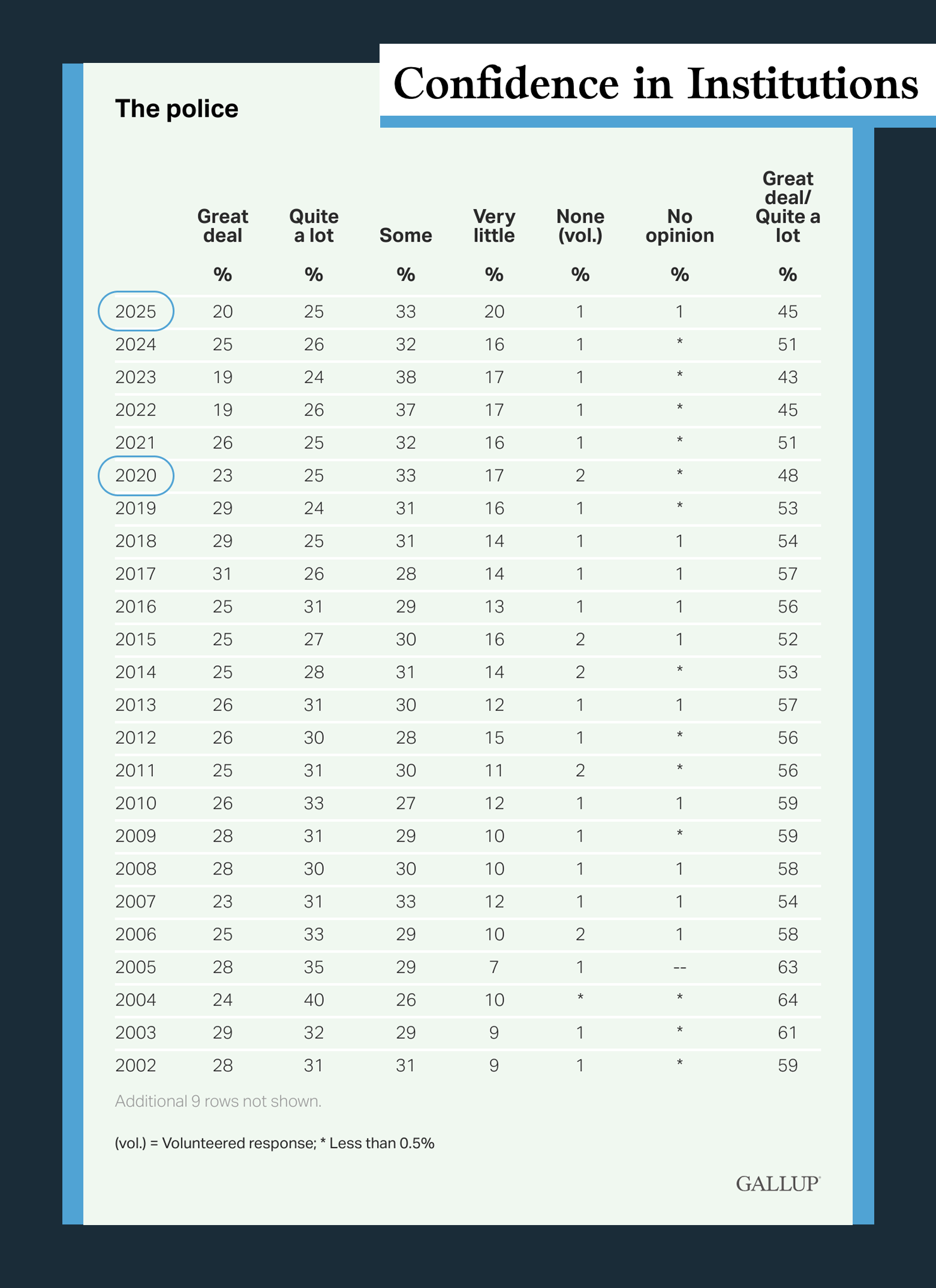

According to Gallup, national polling shows public confidence in policing shifted after 2020, and it hasn’t fully rebounded since. If you ask officers, this strain in community relationships isn’t coming from one moment or one interaction. It’s often being shaped by forces outside the call itself.

National headlines, highly visible federal enforcement activity, and the speed at which incidents circulate on social media all influence how interactions begin, often before an officer has said a word. Even when events happen elsewhere or involve federal agencies, local officers feel the impact in their own communities, where expectations and emotions are already heightened.

Not to pass the buck, that means officers are often starting interactions at a very real disadvantage. They’re asked to build trust in environments shaped by narratives they didn’t create and situations they don’t control.

Efforts like Utah Senate Bill 124 are designed to improve transparency and accountability, and they’ve helped in important ways. But from an officer’s perspective, they don’t always address what’s happening earlier in the process, the small, everyday moments where trust begins to erode long before anything rises to the level of a complaint or formal review.

Without timely feedback or context from the community, officers are left guessing how interactions are landing and where relationships are starting to fray. By the time an issue surfaces through formal channels, the gap has often already widened.

And that leaves officers doing what they’ve always done: showing up, trying to do the right thing, and carrying the weight of that uncertainty from call to call.

4. Burnout From Calls That Never Make the Record

Taken together, these pressures change how the job feels long before anything officially goes wrong. A lot of the work that wears officers down never turns into a report.

Most calls don’t end in an arrest, a complaint, or an incident that shows up in a system. They’re welfare checks, disputes that cool off, conversations that take patience and judgment but leave no paper trail. On their own, they don’t seem significant. Over time, they add up. That’s where burnout often starts.

Officers carry the emotional weight of those interactions, calming people down, absorbing frustration, making quick decisions, without any formal signal that the work happened at all. There’s no metric for a tense situation that didn’t escalate, or a difficult call that ended quietly but took real effort to manage.

Because these moments don’t show up in data, they’re easy to overlook when we talk about workload or stress. But for officers, they’re often the bulk of the job.

Day after day, handling calls that never make the record can start to feel invisible. And when that effort goes largely unseen or unacknowledged, it contributes to burnout in ways that aren’t always obvious until it’s been building for a long time.

5. Feedback Still Arrives Almost Exclusively When Something Goes Wrong

So, now we know that most officers don’t get much feedback day to day. But the real Kicker? When they do, it usually means something didn’t go well.

Complaints, reviews, follow-ups, that’s when feedback shows up. What’s missing is context from the many calls that went fine, felt tense but ended okay, or took real effort to keep from escalating. That creates a weird disconnect.

Even weirder when you dive deep into the data. Our additional feedback surveying conducted in Utah, collected after each interaction, shows positive sentiment in the 84–88% range. With our current systems, officers rarely, if ever see that. What they see, if they see anything at all, comes late.

The picture officers get of their own work is incomplete.

They don’t know when something landed well. They don’t know when a small issue showed up early. They just know when something goes wrong. And over time, that starts to mess with how the job feels. You start assuming silence means you missed something. You replay calls. You carry questions into the next interaction.

Not because you did anything wrong, but because no one ever closes the loop.

Most officers didn’t sign up for constant scrutiny, legal pressure, or trying to interpret national headlines on the fly. They signed up to help their communities and to build something steady over time.

But the job they’re walking into in 2026 carries more weight than it used to, more noise, more uncertainty, and more pressure that shows up before a call even begins.

“My heart goes out to officers right now. I have conversations every week that peel back what the job actually feels like, the quiet stress, the pressure that builds long before anything shows up in a system or a report. What keeps coming up is how much of that weight goes unseen. At Know Your Force, our focus has always been on listening earlier and more often, so officers aren’t carrying all of that alone. When you understand what’s happening in the everyday moments, you’re in a much better position to support the people doing the work.”

- — Scott, Founder, Know Your Force